Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Did you enjoy these videos? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy videos (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Did you enjoy these videos? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy videos (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

On this week’s Proof Points Podcast, Gary explains how seed treatment is an insurance policy to protect yield within a plant. Because we never know what Mother Nature will bring.

Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Did you enjoy these videos? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy videos (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Did you enjoy these videos? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy videos (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

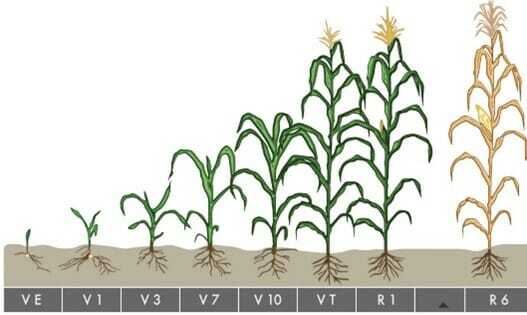

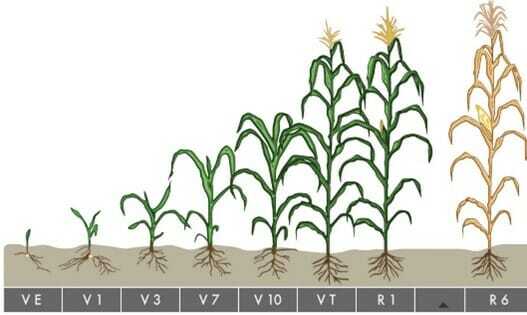

Planting across Latham Country has been progressing at a rapid pace and it will not be long before post-emergence spraying will begin. When to spray, what to spray, should I spray . . . these are some of the questions growers need to consider before heading to the field. I believe “when to spray” is one of the most critical decisions a grower will make. Damaging or injuring a young plant can have lasting affects that may not be visible to the naked eye. Understanding growth stages and relating this to the labeled requirements is a key to successful growing season. Let’s take a look at corn first.

Labels typically refer to growth stages for application timing and the chart below is a good reference.

VE Stage – Corn emergence occurs when the coleoptiles reach and break through the soil surface. Normally, corn requires approximately 100-200 GDUs to emerge, which can be four to five days after planting. At this stage, growth is also taking place below the ground as the nodal root system begins to grow.

Emergence may occur as rapidly as four or five days after planting in warm moist soil, or may take three weeks or more in cool soils. A new leaf will appear about every three days during early growth, while later leaves developing during warmer conditions may appear in one to two days. Full season hybrids in the central Corn Belt typically can produce 21 to 22 leaves. Earlier maturing hybrids will produce fewer leaves.

Keep these numbers in mind as you plan out your season and prepare to spray your fields. Within a month after planting, a corn plant can go from the bag to V5-V7 if conditions are favorable.

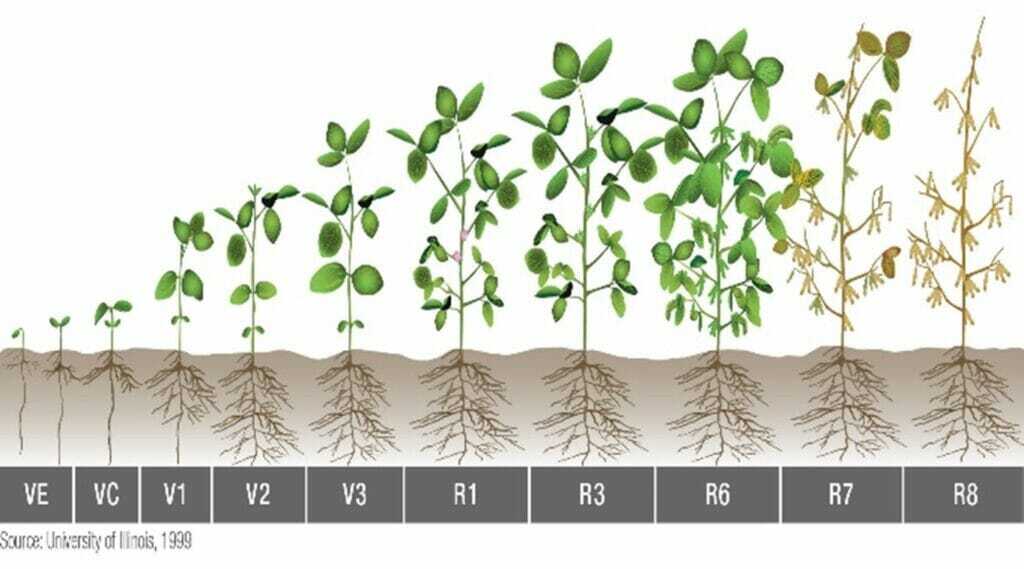

Soybeans in a given field will not be in the same stage at the same time. When staging a field of soybeans, each V or R stage is defined when 50% or more of the plants in the field are in or beyond that stage. This makes it important to understand staging and development since not every plant in the field will be at the same stage when determining application timing. The chart below is a good reference for staging.

The general rule of thumb is to figure five days between growth stages in soybeans. The most important growth stage is R1 which is classified as one flower open at any node on the main stem. Soybean flowers are very sensitive and herbicide application should be avoided at this stage. R1 can begin before canopy closure and the temptation is there to make that final application before canopy closure. A good pre-plant program can help avoid the need for late season spraying and a few late escapes is not worth the consequences from spraying post-flower.

Did you enjoy this article? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy articles (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Did you enjoy these videos? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy videos (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll TALK soon.

Take a look across Latham Country! We’re coming to you every week.

Latham Hi‑Tech Seed’s Corn Plot going in Northern Iowa!

When it’s “go time,” you want to make sure that you have the best alfalfa to fit your field and your end use. Not all alfalfa is created equally, so it pays to give special attention to quality and yield.

Perform a soil test, so you know the soil’s pH, potassium and phosphorous levels. Sulfur and boron levels also factor into forage quality and yield. Alfalfa thrives in well-drained soils with a pH between 6.2 and 7.5. Avoid seeding alfalfa into soils that contain residual herbicides from a previous crop. Seeding alfalfa into existing alfalfa fields is discouraged.

Alfalfa seeding varies widely depending on your location. Seeding in the Upper Midwest can be done from mid-April through May. Seeding in June in the northernmost regions is not uncommon. Seeding early into soils that are too cold may result in delayed emergence, which can cause seedling rot and reduced stands. Planting too late may result in dry topsoil, which can also lead to reduced stands.

Precision planting is not just for corn and soybeans. Alfalfa should be seeded about three-eighths to one-half inch below the soil surface. The ideal stand establishment is between 30 and 35 plants per square foot.

Typical seeding rates for alfalfa seeded without a cover crop are between 12 to 15 pounds per acre. Alfalfa seedlings are very cold tolerant but cannot survive prolonged exposure to freezing temperatures.

High-quality seed is the best step you can take to ensure stand establishment! Look to your local Latham® dealer for help from the start.

Did you enjoy this article? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy articles (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll talk soon.

By the time Latham Hi‑Tech Seeds offers a new corn hybrid, the number of places it has traveled in its developmental process is pretty “a-maize-ing.”

By the time Latham Hi‑Tech Seeds offers a new corn hybrid, the number of places it has traveled in its developmental process is pretty “a-maize-ing.”

Let’s look at the developmental timeline and how your bag of corn seed gets so many frequent flyer miles. It can take at least five years to create a new hybrid with a new seed parent. These new corn lines like to travel. As a breeder, I become the travel agent coordinating their travel plans.

What are some of the popular destinations for these lucky kernels? We use fields in Hawaii, Mexico, Chile and Argentina. By using these countries, we can plant fields year-round to accelerate our development process. In some cases, we can get three growing seasons in one year.

We use these locations to develop new parents, remake successful hybrids, create new experimental hybrids to test each year and produce hybrid for new releases. No one country can efficiently meet all our needs, so using multiple locations allows us to do different processes to deliver a new product to you.

Your family uses passports to travel and gets inspected by the TSA to get on the plane. A corn family needs similar documents for travel. The difference is that your family typically can travel and get into a country within a day. Each seed shipment we send or receive needs its own inspection and unique documentation, depending on where it’s going. Seed is further inspected upon arriving at its destination. This trip can take up to a week or more if its paperwork isn’t accepted. Delays can affect whether the seed arrives home in time.

The next time you look at a bag of Latham brand hybrid seed corn, know that it might have as many airline miles as you do. Unfortunately, I haven’t found a way to collect and use those frequent flyer perks!

Did you enjoy this article? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy articles (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll talk soon.

Like our planting and harvest monitors, corn breeding technologies today improve the speed, accuracy (reliability) and cost of identifying, developing and delivering improved genetics to your farm gate. In this article, I’ll try to briefly describe a few of the most widely used tech tools in developing Latham Hybrids. Like electronic tools, they can be a distraction standing alone, but when linked together into a systematic process they create a powerful platform for continuous improvement.

Unlike traditional methods, “Dihaploid Breeding” (DH) creates homozygous (genetically fixed) male or female corn inbreds quickly. What once took five generations of manual self-pollination can now be created in just two or three generations. Not only do DH’s speed the creation of new inbreds but because they are uniform, they improve and speed field testing required to identify performance. DH delivers inbreds faster (commonly called “instant inbreds”), with near-perfect genetic uniformity at a moderate cost.

Sorting all those new inbreds can become a bottleneck in finding commercially viable candidates. Similar to trying to find NFL players among thousands of college athletes, corn breeding also requires a large pool of candidate inbreds — as quickly as possible. Thankfully, selecting for inbreds with “Favorable DNA” (genes with proven performance) has never been easier or cheaper. Breeders used to spend thousands of dollars to identify a few genetic markers on a single inbred to make associations with key traits such as yield or disease tolerance. Today, we are fast approaching a capability to sequence an entire corn inbred genome (all genes) for less than a dollar. Considering that corn has more genes than humans (on fewer chromosomes), detailed genetic data can enable breeders to quickly select best “candidate” inbreds.

To speed development even further, “Predictive Breeding” can now use genetic data to now simulate some field performance prior to testing in the field. While this will never replace actual field testing predictions, it enables breeders to discard the “chaff” from the wheat — inbreds with low probability of good performance before they’re ever field tested.

Lastly, once commercial lines are identified, “Embryo Rescue” can cycle four generations of trait conversion in the lab and greenhouse in a single year, to deliver trait conversions in two years instead of what used to take four to five years.

None of these tools stand alone, but when paired together they create a powerful process to speed development, improve uniformity and reduce developmental cost of delivering improved Latham genetics to your farm.

Did you enjoy this article? We want to (TECH)talk with you! Sign up for our newsletter to receive agronomy articles (and delicious recipes) in your inbox! We’ll talk soon.