The change from excessively wet to unusually warm, dry weather has resulted in the development of a substantial crust in fields that were previously worked and planted in late April. Obviously, a thick crust can restrict the emergence of corn and cause underground leafing. The rapid drying of the upper soil layer is also conducive for the development of the “floppy corn,” or Rootless Corn Syndrome.

The aforementioned weather pattern may mirror situations across Latham Country this spring, but it’s actually an excerpt from an article that was originally written in May 1998 by an agronomy professor at Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana. Dry surface soils, shallow planting depths, sidewall compaction and cloddy soils all contribute to Rootless Corn Syndrome. Roots will take the path of least resistance, which means they might grow out the bottom of the seed furrow.

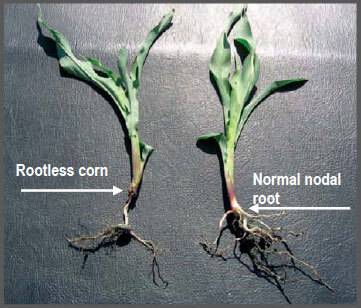

Such corn plants are technically not root-lodged; they are simply broken over at the base of the stem near the crown area. The nodal roots will appear stubbed off but not eaten. The root tips will be dry and shriveled. For a brief description of normal corn root development, click here for R.L. (Bob) Nielsen’s “Primer on Corn Root Development.”

Nodal root growth may resume if more favorable temperatures and moisture conditions return to the fields exhibiting signs of Rootless Corn Syndrome. Cultivation can help by putting soil around the base of plants or aiding in new root development when it does rain. If the ground is hard, cultivation will help with soil aeration.